Manufacturing Distrust in Georgia’s Elections

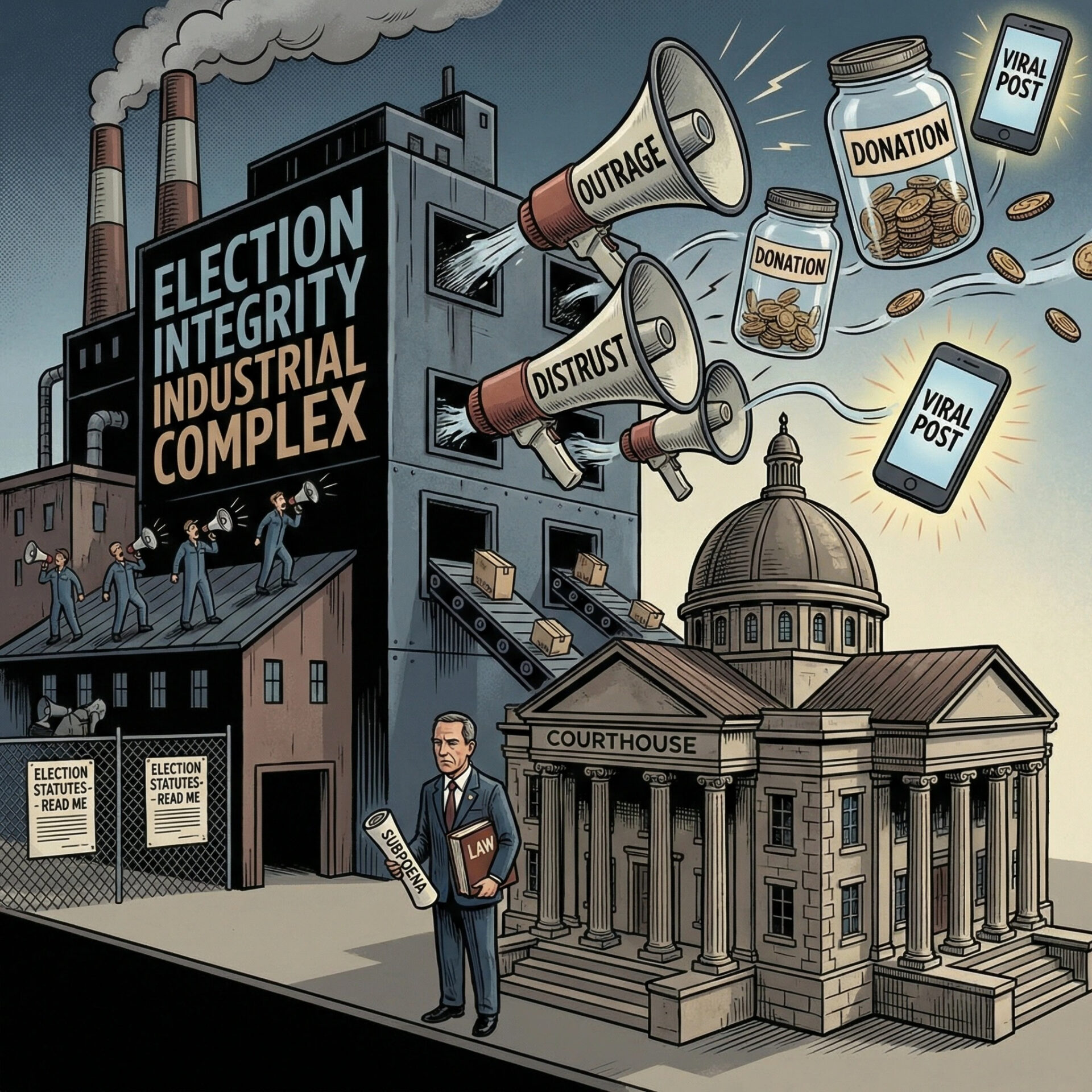

What we are watching unfold in Georgia is not a principled fight over election law, but the latest production of the Election Integrity Industrial Complex™ — the cottage industry of politicians, influencers, and professional outrage merchants who convert distrust in elections into attention, donations, and leverage. For this crowd, lawful process is never the answer; it is the obstacle. When Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger follows Georgia statutes that limit disclosure of sensitive voter data and insists that the federal government use a court order if it wants more, the response is not a legal rebuttal but performative indignation.

The facts of the law don’t matter because the business model depends on conflict, not compliance. Every statute faithfully applied becomes “stonewalling,” every demand for due process becomes “corruption,” and every refusal to break the rules becomes a fundraising email. In that sense, the outrage aimed at Raffensperger isn’t a bug…it’s the product being sold.

Last week, the E.I.I.C. revved back up in Atlanta once again pushing Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to “comply” with a U.S. Department of Justice request for unredacted voter registration data.

Let’s be clear: Raffensperger has complied fully with what Georgia law actually permits. The furor isn’t about secret documents hidden from federal authorities. It’s about activists trying to substitute a preferred political outcome for the rule of law.

Georgia Law Draws a Firm Line Around Voter Privacy

Under Georgia law, specifically O.C.G.A. § 21-2-225, the state’s voter registration list is public, but with important statutory limits on what data is released.

Yes, Georgia legally makes public voter registration lists that include names and residential addresses, party affiliations, precincts, and many other fields that parties, campaigns, and researchers rely on to participate in the democratic process.

But the statute explicitly prohibits disclosure of:

- Full dates of birth (month and day),

- Social Security numbers or partial SSNs,

- Driver’s license numbers,

- Certain other sensitive data.

These aren’t Raffensperger’s own “privacy preferences.” They are bindings written into state law by the legislature itself.

Members of the public and private sector routinely purchase and use these voter lists because they already include names and addresses, the same kinds of openly releasable data that party organizations and campaigns have long used without controversy.

Address Confidentiality Isn’t Optional, It’s Required

What often gets no attention in the peanut gallery is that Georgia also protects certain residential address data by statute for people who, by law, need those protections.

The Georgia VoteSafe program, enacted by the legislature, allows voters who have been or may be subject to family violence, stalking, or similar threats to keep their actual residence addresses off public lists, even while remaining fully registered and able to vote.

This isn’t guesswork. It’s an intentional policy; addresses of individuals with protective orders or who reside in family-violence shelters must remain confidential “at all times from public disclosure.”

That means Judges, crime victims, stalking victims, and others with legitimate safety concerns aren’t exposed to additional risk because someone wants political points. That’s not “political correctness.” That’s reasonable privacy protection written into Georgia law.

Other states have similar programs. Raffensperger didn’t invent this. He’s obligated to follow it.

Raffensperger Has Shared What the Law Allows and the Law Is Not Optional

Raffensperger’s office has already transmitted all legally releasable records to the DOJ, including the voter registration list and documentation of list maintenance efforts.

The Department of Justice, under the current administration, has turned that into a lawsuit in federal court in Macon, demanding unredacted data, including full addresses, driver’s license numbers, and partial Social Security numbers.

This isn’t some arcane procedural dispute. Federal statutes such as the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) and the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) certainly address list maintenance, but they do not automatically repeal Georgia’s own privacy statutes. DOJ clearly thinks they do – Georgia law says otherwise.

If the DOJ truly believed it had the right to this data, the appropriate legal path is through a federal court subpoena or order, not a press release or political pressuring of a state official. That’s how federalism and the rule of law work.

Raffensperger’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit makes just that point: a court, not a resolution and not a press conference, must decide whether the federal request overrides state privacy protections.

Public Data, Private Data: Raffensperger Draws the Line Where the Law Draws It

To his credit, Raffensperger hasn’t tried to claim that nothing in the voter list should be public. He has correctly acknowledged that what parties, candidates, and researchers already get is the public voter list. That includes names and addresses under normal circumstances (and even then, addresses of protected voters are withheld).

This is vital context the resolution sponsors ignore:

- The publicly available list is legally publishable.

- Sensitive information is legally protected.

- Certain individuals’ addresses are required by law to be withheld for safety reasons.

And yet, here we have politicians who themselves voted for the law are now attacking an official for following it.

Raffensperger’s stance is simple: Georgia will share what Georgia law allows, and anything beyond that requires proper legal process. That is the right answer—whether you love him, hate him, or are just tired of politicians using voters’ private information as a political football.

A Baseless Claim, a Real Legal Process

Those pushing this argue that Raffensperger is obstructing the highest law enforcement agency in the land. They’re wrong. What they’re really doing is conflating political pressure with the legal authority to compel disclosure.

If the federal government wants data that Georgia law prohibits it from releasing, it should have filed the subpoena first and let a judge decide. That’s not obstruction…that’s due process.

Rebuttal: “The Federal Government Already Has Our Social Security Numbers”

Critics argue that Georgia’s voter-data protections are pointless because the federal government already possesses Social Security numbers. That misses the point — legally and practically.

First, possession is not permission. The fact that one federal agency lawfully holds Social Security numbers for a specific purpose does not authorize the Georgia Secretary of State to release the same data from a completely different system. Georgia law governs what Georgia officials may disclose, and those limits do not disappear simply because someone else might already have similar information elsewhere.

Second, custodianship matters. When Georgia collects voter data, the Secretary of State becomes its legal custodian. That role carries statutory duties to safeguard sensitive information and restrict disclosure. Once such data is transferred, Georgia loses control over how it is stored, accessed, or shared. That loss of control — not mistrust — is exactly why disclosure limits exist.

Third, aggregation is the real risk. A voter file combining names, addresses, driver’s license numbers, and partial Social Security numbers is far more sensitive than those data points scattered across separate agencies for unrelated purposes. Georgia law deliberately prevents that kind of bulk aggregation because it increases the risk of misuse, breach, or secondary disclosure…regardless of who requests it.

Finally, “trust us” is not a legal standard. If the Department of Justice believes federal law entitles it to data that Georgia law protects, the remedy is simple:

Obtain a federal court order.

That process allows a judge to define scope, impose safeguards, and balance federal authority against state privacy protections.

Skipping that step isn’t efficiency…it’s ignoring the law.

Once again, Raffensperger’s refusal isn’t obstruction. It’s adherence to the statutes he is sworn to enforce, and a reminder that privacy protections mean little if they vanish the moment they become inconvenient.

Let’s Stop Weaponizing Elections

What’s happening here is not principled governance. It’s not even a coherent legal argument. It is political theater dressed up as accountability by those who comprise Georgia’s E.I.I.C.

Raffensperger’s critics, including those in his own party, seem to think that “because DOJ asked for it” that’s enough to override state privacy law.

It isn’t.

The law isn’t a suggestion. And the privacy of ordinary Georgians, whether Republicans, Democrats, or Independents, and especially vulnerable voters whose addresses are shielded by statute, is worth defending.

Raffensperger isn’t blocking transparency. He’s enforcing the law as written and insisting that proper legal process, including a federal court order, if necessary, is the avenue for anything beyond what Georgia statutes allow.

That’s not obstruction. That’s responsibility.