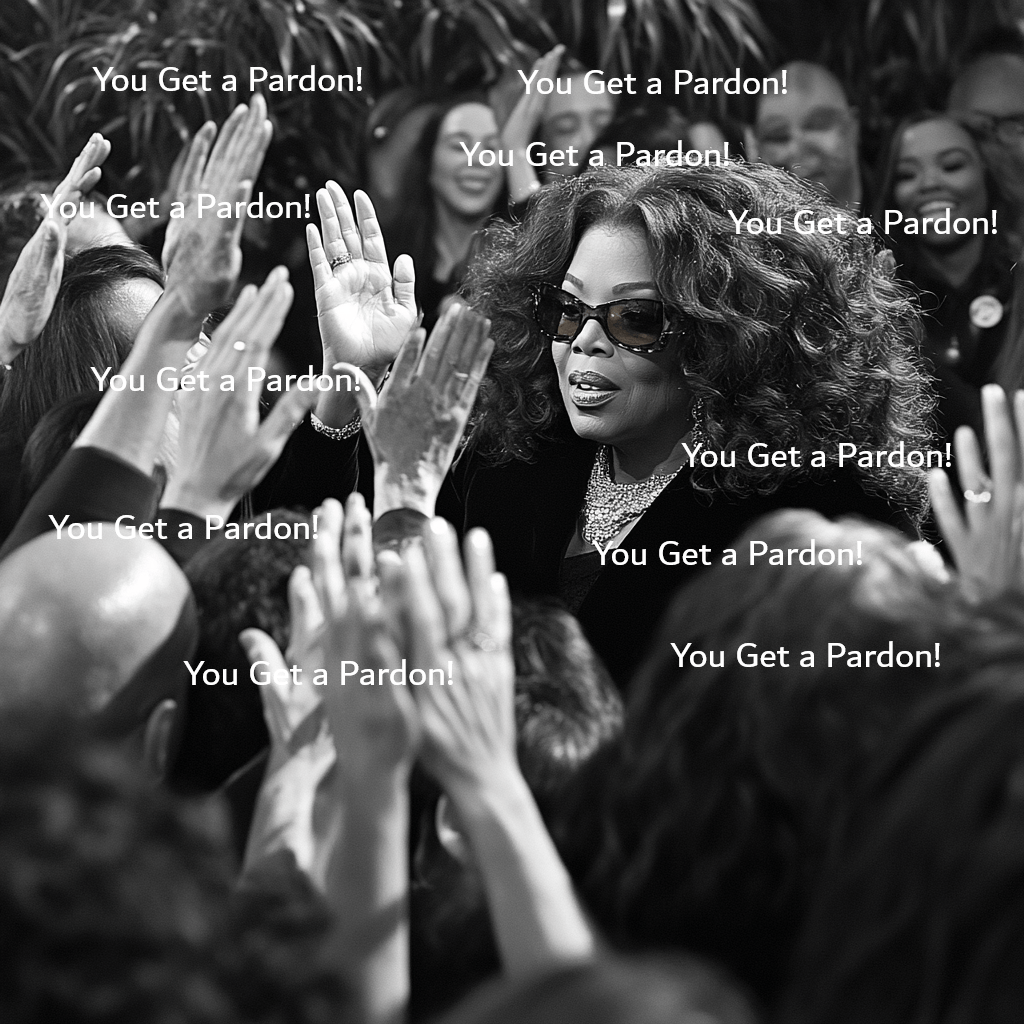

Biden: You Get a Pardon! And You Get a Pardon! Trump: You Get a Pardon! And You Get a Pardon!

The Scene: December, 2020. President-Elect Biden sits with Jake Tapper for an interview on CNN.

Tapper: President Trump is reportedly considering a wave of preemptive pardons for his adult children and for Rudy Giuliani. He’s also floated the idea in private conversations according to our reporting of possibly pardoning himself, which he insists he has the power to do although that has never been litigated. Does this concern you? All of these preemptive pardons?

Biden: Well, it concerns me in terms of what kind of precedent it sets and how the rest of the world looks at us as a nation of laws and justice.

Cut Scene to January 20th, 2025. Joe Biden, in his final hours in office, signs preemptive pardons for his family members. I do hope that someday history will not be giving him a pass for this like the modern day media seems to be doing. I cannot stand hypocrisy.

Justifiably and understandably, my friends on the right were outraged.

Here’s a sample of things I saw in my various feeds:

- So, the most corrupt (and worst) President in our Country’s history just preemptively pardoned Fauci, Gen Milley, and the Jan 6th cmte. Aren’t pardons for people who actually committed crimes? Why would these people need pardons?

- Nothing screams GUILTY louder than a pardon for uncharged crimes.

- On a picture of Anthony Fauci: Nothing says “Trust the Science” quite like a preemptive pardon.

- Ya don’t need to pardon the innocent.

- How can someone be legally pardoned for unspecified crimes? To those who support this…what if it were Trump doing it?

- How do you tell the world that someone (or in today’s example, several “someones”) is a criminal without telling everyone that they are a criminal? Apparently, it’s a piece of cake… Just pardon a whole group of people who haven’t been charged or convicted of a crime. Sadly, many will look the other way and quickly forget.

- If you’re not guilty of any crimes you don’t need a preemptive pardon!

Again, in my opinion, their outrage is justified. And by noon the flood of posts were singing with a single voice. And since I am not up to speed on the whole pardon thing, I began to research the history and case law relating to pardons and how they work. That is not to say that I am expert in any way whatsoever, but I found cases and curated them here for your reference.

But first, some facts I learned along the way:

A presidential pardon in the United States is a constitutional power granted under Article II, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution. While this power is broad, there are specific contexts and legal questions where its application can be scrutinized. Here’s how and when a presidential pardon could potentially be challenged:

1. Pardons Cannot Be Overturned by Courts

- Supreme Authority: The pardon power is exclusive to the president and generally not subject to judicial review.

- Courts cannot invalidate a pardon based on disagreements with the president’s decision.

2. Situations Where Pardons May Face Legal Challenges

- Unconstitutional Purpose: If a pardon were issued as part of a corrupt act (e.g., bribery, obstruction of justice), it won’t invalidate the pardon itself but could expose the president to legal consequences for the corrupt act.

- Violations of Other Laws: A pardon cannot violate constitutional principles like equal protection or due process. For example, if a pardon were explicitly discriminatory, it could be challenged on those grounds.

3. Acceptance of a Pardon

- A pardon must be accepted by the recipient to take effect. If the recipient refuses the pardon, its legal implications are moot.

4. State Crimes

- No Protection from State Charges: A presidential pardon only applies to federal offenses. States can still prosecute individuals for violations of state law, regardless of a federal pardon.

5. Congressional Oversight

- Political Accountability: While Congress cannot directly overturn a pardon, it can investigate the circumstances surrounding it, especially if corruption or abuse of power is suspected. This could lead to impeachment proceedings if the pardon is part of broader misconduct.

And now for the cases that inform those conditions:

1. Ex parte Garland (1866)

- Key Issue: The extent of the president’s pardon power.

- Ruling: The Supreme Court held that the president’s pardon power is “unlimited” and extends to any federal offense, whether before, during, or after legal proceedings.

- Significance: This case firmly established the breadth of the pardon power, confirming that it applies even to offenses not yet prosecuted.

2. United States v. Klein (1871)

Key Issue: The interaction between the pardon power and congressional action.

- Ruling: The Court invalidated a law passed by Congress that attempted to restrict the legal effect of presidential pardons.

- Significance: This case reinforced that Congress cannot limit or interfere with the president’s pardon power.

3. Burdick v. United States (1915)

Key Issue: Whether a pardon can be forced upon someone.

- Ruling: The Court ruled that a pardon must be accepted to take effect, and the recipient has the right to refuse it.

- Significance: This case clarified that a pardon is not an imposition but an offer that can be declined, as acceptance implies an acknowledgment of guilt.

4. Schick v. Reed (1974)

- Key Issue: Whether conditions can be attached to a pardon.

- Ruling: The Court held that the president can issue conditional pardons as long as the conditions do not violate the Constitution.

- Significance: This confirmed the president’s ability to impose reasonable conditions on pardons.

5. Murphy v. Ford (1975)

- Key Issue: The validity of a pardon issued for “unindicted crimes.”

- Ruling: A federal district court (not SCOTUS) upheld President Gerald Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon for any crimes he may have committed during his presidency.

- Significance: Though not a SCOTUS case, it affirmed the president’s power to issue a pardon for unprosecuted offenses to promote national interests, like healing political divisions.

6. Trump v. Vance (2020)

- Key Issue: The limits of the president’s immunity and the reach of state prosecution.

- Ruling: The Court ruled that the president is not immune from state criminal investigations, emphasizing the distinction between federal and state offenses.

- Significance: While not directly about pardons, this case reinforced that a presidential pardon cannot shield someone from state-level criminal charges.

It is currently accepted that a pardon must be accepted and may be rejected by the recipient. The acceptance of a pardon indicates an admission of guilt, although under the current circumstance that may be, in my opinion, an outdated perspective. Reason being that when it became practice that accepting a pardon is an admission of guilt we didn’t experience the kind of weaponization of the justice system we see today.

The left has a deep seated fear that Trump would fabricate charges against his enemies. Regardless whether that fear is real they certainly believe it, and frankly his public comments have fueled those fears. Also, this is a nice little cover story for any actual crimes they may have committed.

If there were crimes committed by the Bidens, no one will spend the resources to find them because they cannot be prosecuted anyway, and that may be the goal if I am engaging in wild speculation.

The 1866 Supreme Court decision in Ex parte Garland serves as the foundation for understanding the breadth of the presidential pardon power. In this case, the Court affirmed that the president’s power to pardon is “unlimited” and applies to offenses committed at any stage—before, during, or after prosecution. This expansive interpretation paved the way for controversial uses of the pardon power, such as Gerald Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon for any crimes he may have committed during the Watergate scandal. Crimes for which Nixon was never charged. Similarly, it supports the legality of preemptive pardons by any president, including hypothetical or actual pardons for family members like we saw from Joe Biden on Inauguration Day.

In short, Joe Biden had the power to do what he did and there was precedent (Nixon) for him to pardon unspecified and uncharged crimes. But I am not saying that was the right thing to do. It was quite the opposite.

By evening on Inauguration Day, Trump had given out pardons to the J6 Rioters. But here is the sticky part; my feed has been filled for years with calls for pardons for the people who stormed the Capitol on J6. Many of these calls claim that many of the people accused of crimes, “Didn’t do anything wrong!” Some have taken to calling these people the “J6 Hostages,” which makes me throw up in my mouth a little.

Certainly it can be said that not everyone who was in the Capitol that day was a rioter or had violent intentions. Some found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. But there were a large number who had nothing but violence on their mind. Trump issued about 1500 pardons for those folks, including the violent offenders.

On J6 Daniel Rodriguez and five others repeatedly used a stun gun to shock Capitol Police Officer, Michael Fanone, so many times that Fanone lost consciousness and had a heart attack. The mob continued to beat him in a tunnel while he was unconscious, ending his law enforcement career. Rodriguez was sentenced to 12 years in jail on four felony charges.

Fanone did not hold back when criticizing President Trump’s pardon of Rodriguez, saying, “I have been betrayed by my country. And I have been betrayed by those who supported Donald Trump. Whether you voted for him because he promised these pardons or for some other reason. You knew that this was coming and here we are. Tonight, six individuals who assaulted me as I did my job on January 6th, as did hundreds of other law enforcement officers, will now walk free. Six individuals who have threatened my life and who have made threats towards my family members. My family, my children, and myself are less safe today because of Donald Trump and his supporters.”

His words not mine.

So playing the role of pudding stick, I posted the following on my socials today: “So those January 6th pardons are an admission of guilt, right? Social media said you don’t need a pardon if you did nothing wrong. So they are now admitting they did something wrong? Right?

Also, did I mention I cannot stand hypocrisy?

An eagle eyed friend pointed out there was a case that may throw a wrinkle into that thought process. A quick primer:

The Case of Clint Lorance: A Challenge to the Burdick Doctrine

Fast forward to 2021, and the legal landscape surrounding presidential pardons takes an intriguing turn with Lorance v. Commandant, U.S. Disciplinary Barracks. Clint Lorance, a former U.S. Army officer convicted of second-degree murder during his service in Afghanistan, received a presidential pardon from Donald Trump in 2019. But despite accepting the pardon, Lorance didn’t stop there. He sought to challenge his court-martial conviction through a habeas corpus petition.

In a notable decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit ruled in Lorance’s favor, declaring that accepting a pardon does not automatically equate to a confession of guilt. The court permitted Lorance to continue his habeas challenge, effectively dismantling the notion that a pardon inherently nullifies an individual’s right to contest their conviction. This ruling stands in stark contrast to the implication in Burdick v. United States that accepting a pardon is tantamount to acknowledging guilt.

It’s important to note that Lorance’s case did not make its way to the Supreme Court. Instead, the proceedings ended with the Tenth Circuit’s decision, which affirmed that accepting a pardon neither constitutes a legal confession of guilt nor eliminates the right to pursue habeas corpus relief. This interpretation allows Lorance, and potentially others in similar situations, to continue challenging their convictions even after receiving a presidential pardon.

With the Supreme Court yet to review this specific issue, the Tenth Circuit’s ruling remains the prevailing interpretation within its jurisdiction. Still, it’s a significant development in the ongoing conversation about the implications of clemency.

While Burdick continues to serve as a foundational precedent, its interpretation of pardons as an admission of guilt has evolved. The Lorance decision highlights a more nuanced understanding of clemency in today’s legal framework. Modern courts are increasingly willing to consider the broader context of a pardon—whether it’s granted for political, pragmatic, or humanitarian reasons—and recognize that accepting a pardon doesn’t always mean accepting culpability.

As someone deeply interested in the erosion of public trust in American institutions, I can’t help but see these cases as emblematic of broader questions about transparency, fairness, and the rule of law. And you may find yourself shocked that both sides are, at the very least, using the pardon power in a ham-fisted manner that the other side will criticize. However, when a pardon is issued, especially in politically charged cases, it often raises eyebrows. How do we reconcile the president’s broad power to pardon with the public’s expectation of accountability? And how do we balance the intent of a pardon with its legal and societal implications?

In the mean time, maybe we worry a little less about what the other side is doing and make sure our own side isn’t creeping towards abusive use of power.